Sacred Seasons, Authority, and the Struggle to Preserve Alignment

1. Introduction: calendar drift as a biblical, not modern, problem

Calendar drift is often treated as a technical issue emerging with medieval or early-modern chronology. In fact, drift is already a biblical problem, embedded in the way Israel’s worship binds together lunar months, agricultural seasons, and covenantal memory. Because Israel’s festivals are seasonally anchored yet lunar-dated, sacred time required continual alignment. Where alignment weakened, disagreement followed; where authority fractured, calendars pluralised.

This post traces how drift shaped biblical practice, institutions, and interpretation—from Exodus to the Second Temple period—and why managing drift became a theological task.

2. Passover and the month of Aviv: drift resisted in Scripture

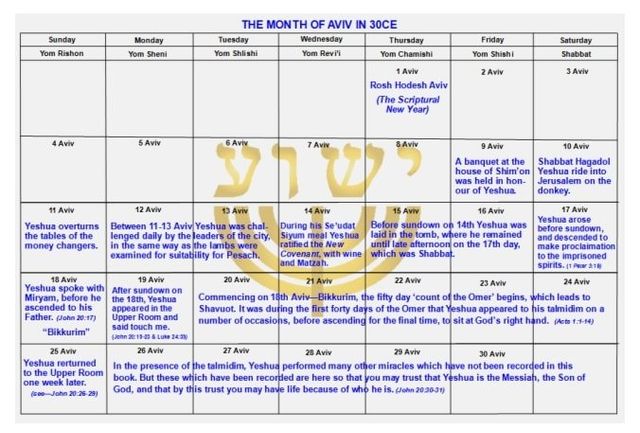

2.1 Aviv as an agricultural criterion

In Exodus 12:2 and 13:4, Passover is fixed to the month of Aviv. Aviv denotes ripening barley, not a numerical month. This is decisive: barley ripens only in spring. A purely lunar calendar would push Passover into winter within a few years. Scripture therefore presupposes intercalation—the insertion of an extra month when the crop is not ready.

The biblical text embeds an anti-drift requirement without technical language: sacred time must align with created seasons (Stern, 2012).

2.2 Observation and declaration

Early Israelite practice combined:

- lunar observation (new moons),

- agricultural inspection (barley readiness),

- authorised declaration (community/priestly leadership).

Calendar keeping was thus an act of obedience, not mere astronomy.

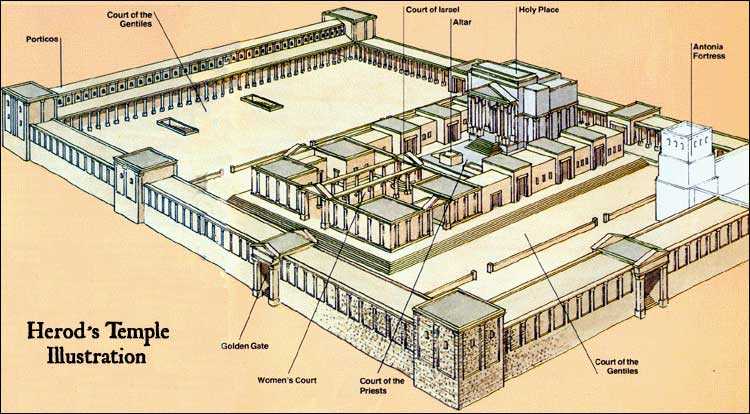

3. Centralised authority: Jerusalem as calendrical arbiter

During the monarchic period, calendrical authority increasingly centred on Jerusalem and the Temple. Centralisation stabilised festival timing and sacrificial cycles. Stability, however, depended on political sovereignty, uninterrupted cult, and uncontested priestly authority. When these conditions failed, drift re-emerged—not astronomically, but institutionally.

4. Exile and dispersion: when drift becomes unavoidable

The Babylonian exile (sixth century BCE) dismantled the calendrical infrastructure:

- the Temple was destroyed,

- central observation was disrupted,

- communities dispersed geographically.

While the weekly Sabbath continued unchanged, festival alignment became vulnerable. Local communities relied on their own observations or traditions, introducing plurality. Drift here reflects loss of jurisdiction, not loss of knowledge.

5. Second Temple Judaism: multiple calendars, contested legitimacy

5.1 Evidence from Qumran

The Dead Sea Scrolls attest a 364-day solar calendar used by the Qumran community. This system:

- fixed festivals to weekdays,

- rejected lunar months and intercalation,

- accused Temple authorities of corrupting sacred time.

Temple authorities, by contrast, maintained a lunisolar system. The disagreement was theological: calendar choice signalled covenantal fidelity (VanderKam, 1998).

5.2 Calendar as boundary marker

Calendrical difference functioned as a marker of identity and legitimacy. Who controlled time controlled worship.

6. The Gospels and Passover chronology

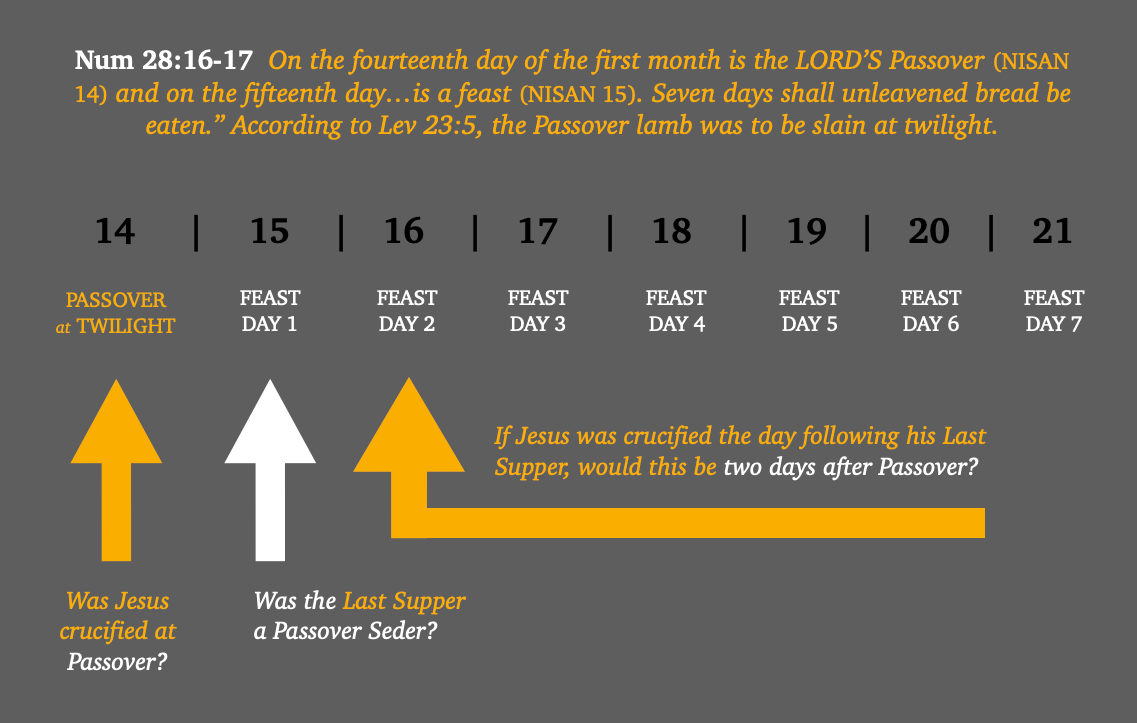

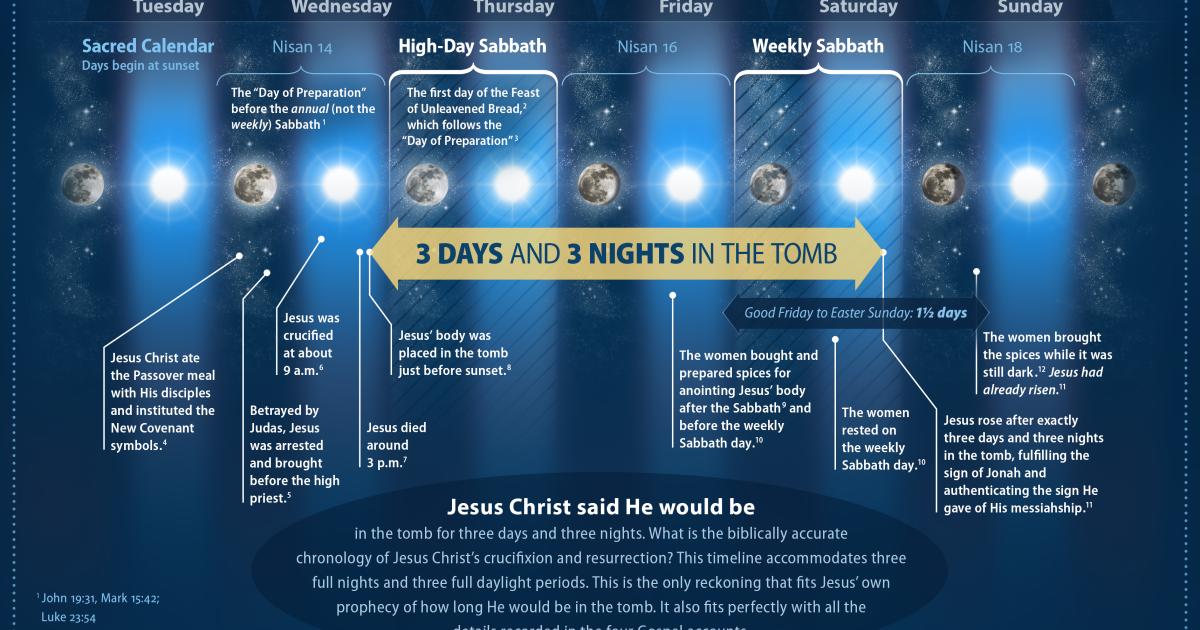

The New Testament preserves a well-known tension:

- the Synoptics present the Last Supper as a Passover meal,

- John places the crucifixion before Passover.

Rather than a simple contradiction, many scholars interpret this as evidence of coexisting calendars within late Second Temple Judaism. Different groups reckoned Passover on different days under different authorities (Vermes, 2011). Drift and plurality provide a historically coherent explanation.

7. Early Christianity: inherited drift and the Easter problem

The early Church inherited:

- Jewish festival theology,

- Roman civil time,

- unresolved calendrical plurality.

As Christianity expanded, reliance on Jewish declarations proved impractical. The Church therefore adopted calculated rules for Easter, privileging unity over local observation. This move managed inherited drift but introduced complexity—later manifesting in East–West divergence (Richards, 2013).

8. What biblical history reveals about drift

Biblical history shows that:

- drift was anticipated within Scripture,

- alignment required recognised authority,

- exile intensified plurality,

- unresolved drift generated theological conflict.

Sacred time demanded governance. Astronomy alone was insufficient.

9. Concluding insight

Calendar drift shaped biblical history because Israel’s worship bound memory, seasons, and obedience together. When authority was unified, drift was managed; when authority fractured, time itself became contested. Drift is thus not peripheral to biblical faith—it is a lens on covenant, authority, and alignment.

References

Richards, E.G. (2013) Mapping Time: The Calendar and Its History. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Stern, S. (2012) Calendars in Antiquity: Empires, States, and Societies. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

VanderKam, J.C. (1998) Calendars in the Dead Sea Scrolls: Measuring Time. London: Routledge.

Vermes, G. (2011) Christian Beginnings: From Nazareth to Nicaea. London: Penguin.