Incommensurable Cycles, Competing Authorities, and the Logic of Disagreement

1. Introduction: disagreement as a structural outcome

The non-alignment of religious dates—why festivals “move,” why traditions disagree, and why the same observance may fall on different days across communities—is often attributed to confusion or error. In fact, such disagreement is structurally inevitable. It arises from the attempt to integrate incommensurable temporal cycles (solar, lunar, weekly) under different authorities and distinct theological priorities.

This post explains the mechanics of calendrical disagreement and shows why alignment across traditions is not merely difficult, but impossible without abandoning core commitments.

2. The foundational mismatch: solar year vs lunar month

Two astronomical facts govern most religious calendars:

- Tropical (solar) year: ≈ 365.2422 days

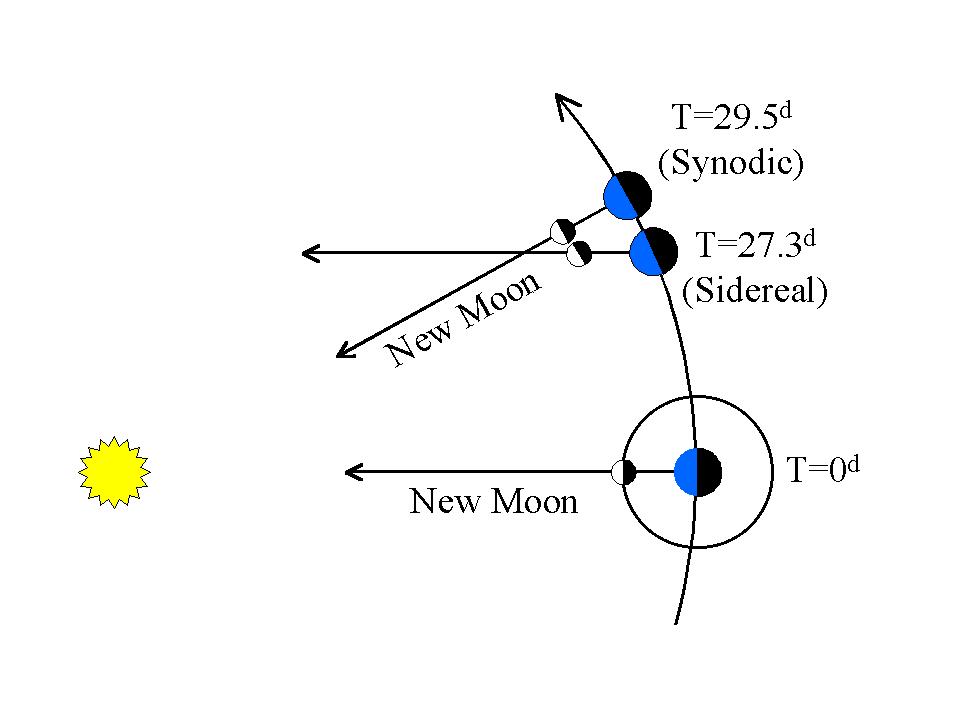

- Synodic (lunar) month: ≈ 29.53059 days

Twelve lunar months total ≈ 354.37 days, leaving an annual gap of ≈ 10.87 days relative to the solar year. Over time, this gap accumulates into full months and seasons. Any calendar that preserves lunar months must therefore choose between:

- correction (to preserve seasons), or

- acceptance of drift (to preserve lunar purity).

Different religions make different choices—and dates diverge accordingly (Stern, 2012).

3. Three strategies, three outcomes

3.1 Solar anchoring (fixed seasons, variable moons)

Example: Gregorian calendar

Solar calendars stabilise seasons by inserting leap days. Lunar coherence is sacrificed. Religious dates tied to fixed civil dates (e.g. Christmas on 25 December) remain seasonally stable but drift relative to lunar phases.

Outcome: Administrative and seasonal consistency; lunar disconnection.

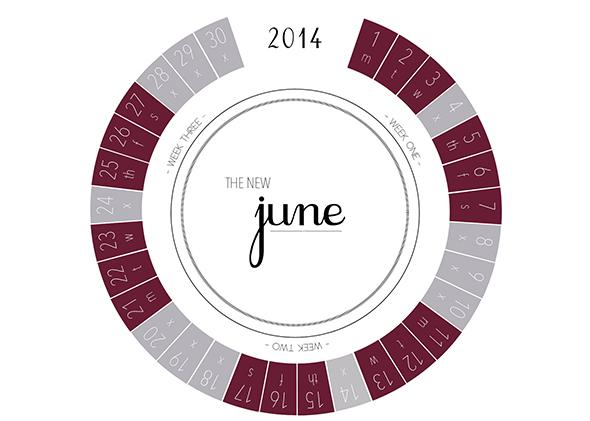

3.2 Lunisolar correction (fixed seasons and moons, complex rules)

Example: Hebrew calendar

Lunisolar calendars preserve lunar months and seasonal placement by inserting leap months (e.g. seven times in a 19-year Metonic cycle). This keeps festivals such as Passover in spring, as required by Scripture.

Outcome: Seasonal fidelity at the cost of computational and institutional complexity (Stern, 2012).

3.3 Pure lunar reckoning (fixed moons, rotating seasons)

Example: Islamic (Hijri) calendar

Pure lunar calendars add no correction. Months are determined by moon sighting; festivals rotate through all seasons over ~33 years.

Outcome: Ritual purity and simplicity; deliberate seasonal drift (King, 2008).

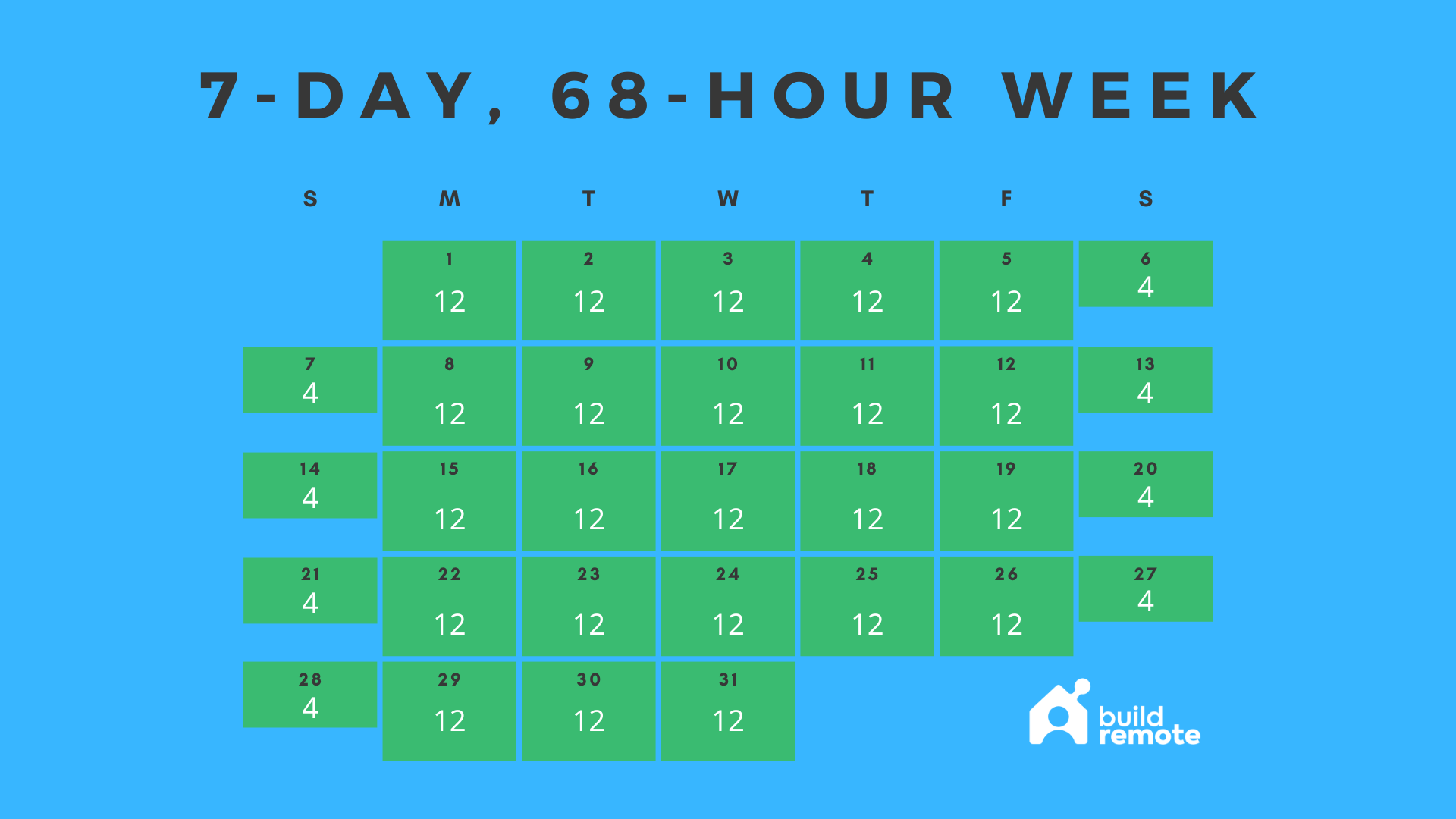

4. The week: a non-astronomical constraint that never moves

The seven-day week introduces a further constraint:

- it has no astronomical basis,

- it does not divide evenly into months or years,

- it repeats continuously without correction.

Because most religious traditions refuse to alter the weekly rhythm, disagreement compounds when festivals must satisfy both a lunar/solar rule and a weekly rule (e.g. “Sunday”). This is a primary reason complex rules are required for dates such as Easter (Zerubavel, 1985).

5. Observation vs calculation: why communities within the same religion disagree

Beyond astronomy, disagreement arises from method.

5.1 Observational calendars

- Depend on sighting (moon, crops).

- Vary by location and weather.

- Require local authority.

5.2 Calculated calendars

- Use tables and algorithms.

- Enable advance planning and global uniformity.

- Introduce approximation error over time.

Disputes arise when communities prioritise local realism (what was seen) versus institutional uniformity (what the table declares). This explains why the same festival may be celebrated on different days even within a single tradition (Stern, 2012).

6. Authority and jurisdiction: alignment within, divergence without

Calendars align internally because an authority enforces a rule set. They diverge externally because authorities differ.

- A religious court, council, or scholarly tradition must decide:

- when a month begins,

- whether correction is required,

- which approximation is acceptable.

Once jurisdictions separate, dates diverge—even if the underlying astronomy is shared. Disagreement is thus jurisdictional, not scientific.

7. Case study: why Easter exposes the problem

Easter integrates three constraints:

- Lunar (after the full moon / Passover),

- Solar (spring / equinox),

- Weekly (Sunday).

No single astronomical event satisfies all three. The Church therefore employs an authorised approximation (computus), fixing:

- an ecclesiastical equinox (21 March),

- an ecclesiastical full moon,

- a Sunday rule.

Because different jurisdictions adopt different calendar baselines (Gregorian vs Julian), Easter often falls on different dates across Christian traditions—without any party “miscalculating” (Bradshaw and Johnson, 2011; Richards, 2013).

8. Why universal alignment is impossible

Universal alignment would require:

- a single authority,

- a single correction method,

- agreement on which cycles matter most.

Achieving this would force at least one tradition to abandon a non-negotiable commitment (seasonal anchoring, lunar purity, weekly rhythm, or jurisdictional autonomy). Disagreement, therefore, is the price of fidelity.

9. Concluding insight

Religious calendars do not disagree because they are poorly designed, but because they are faithful to different priorities. Dates move and diverge because time itself does not divide cleanly—and because communities refuse to let what they consider sacred be subordinated to convenience.

Calendrical conflict is not a bug. It is the visible trace of competing authorities over time.

References

Bradshaw, P.F. and Johnson, M.E. (2011) The Origins of Feasts, Fasts and Seasons in Early Christianity. London: SPCK.

King, D.A. (2008) In Synchrony with the Heavens: Studies in Astronomical Timekeeping and Instrumentation in Medieval Islamic Civilisation. Leiden: Brill.

Richards, E.G. (2013) Mapping Time: The Calendar and Its History. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Stern, S. (2012) Calendars in Antiquity: Empires, States, and Societies. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Zerubavel, E. (1985) The Seven Day Circle: The History and Meaning of the Week. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.