The Mechanics Behind Timekeeping and Why It Refuses to Behave Neatly

1. Introduction: astronomy constrains, culture organises

Calendars appear deceptively simple: a sequence of days grouped into weeks, months, and years. In reality, calendars are compromise machines. They attempt to reconcile astronomical cycles that do not divide evenly with social rhythms that demand regularity. Understanding how calendars work therefore requires distinguishing natural units of time from conventional structures imposed upon them.

This post explains what each unit of time represents, why these units are incompatible, and how different calendar systems manage—rather than solve—the resulting tensions.

2. The day: the only unavoidable unit

2.1 Astronomical basis

The day is defined by the Earth’s rotation on its axis relative to the Sun. Unlike other units, it is:

- directly observable,

- physically inevitable,

- universally recognised.

Although cultures historically subdivided the day differently (e.g. variable-length hours in antiquity), the existence of the day itself never required correction (Richards, 2013).

2.2 Implication

The day is ontologically stable. All calendars must accept it as a given starting point.

3. The month: lunar regularity, solar incompatibility

3.1 Astronomical basis

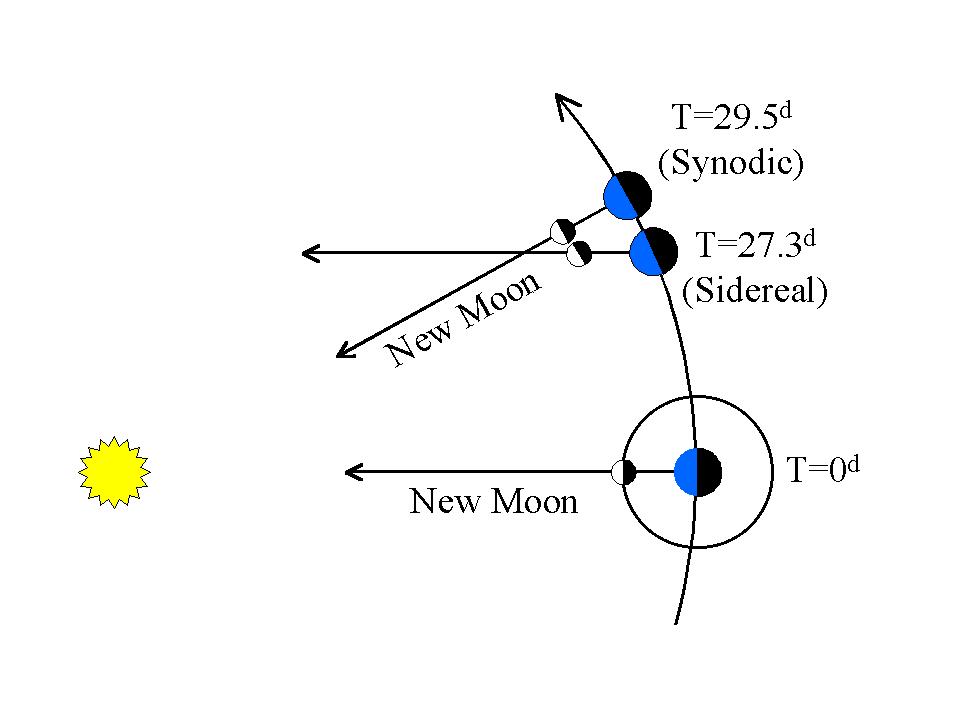

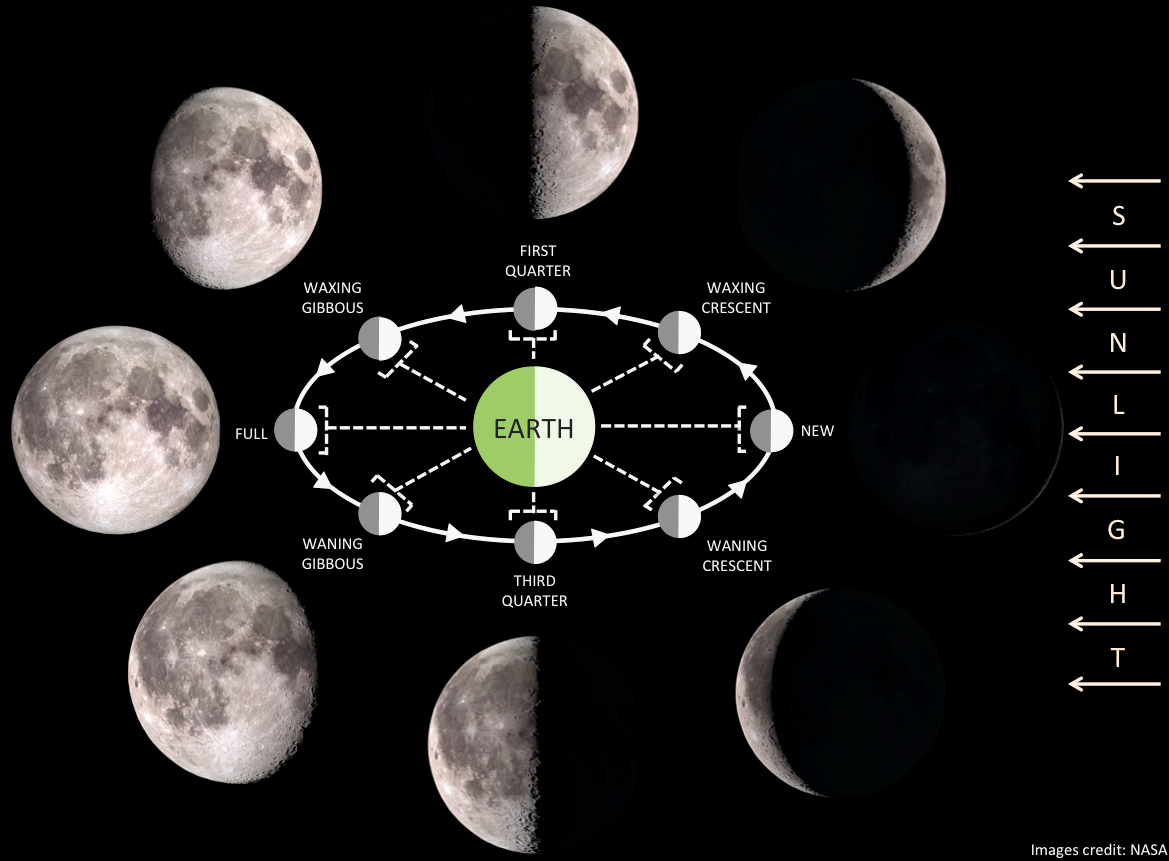

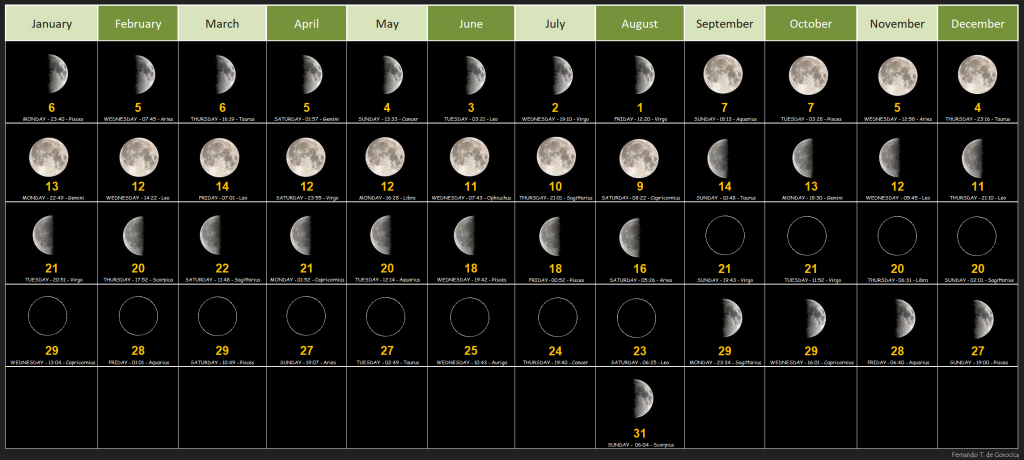

A lunar (synodic) month corresponds to the Moon’s cycle of phases:

- approximately 29.53059 days.

Because this value is not an integer:

- months must alternate between 29 and 30 days,

- fractional time accumulates immediately.

3.2 Structural problem

Twelve lunar months equal roughly 354 days, which is about 11 days shorter than the solar year. Without correction, months drift rapidly through the seasons.

Calendars that preserve lunar months must therefore choose between:

- accepting seasonal drift, or

- inserting corrective mechanisms (Stern, 2012).

3.3 Implication

The month is internally regular but externally unstable.

4. The year: solar dominance and correction

4.1 Astronomical basis

The tropical (solar) year—the cycle governing seasons—is approximately:

- 365.2422 days.

No calendar can represent this value exactly using whole days.

4.2 Calendar responses

Different systems preserve the year in different ways:

- Solar calendars (e.g. Gregorian): add leap days.

- Lunisolar calendars (e.g. Hebrew, Chinese): add leap months.

- Pure lunar calendars (e.g. Islamic): add no correction and allow drift.

Each strategy protects a different priority: seasons, festivals, or ritual purity (Richards, 2013).

4.3 Implication

The year is astronomically authoritative but structurally unstable without artificial intervention.

5. The week: a social rhythm that outlived astronomy

5.1 Origin and nature

The seven-day week has no direct astronomical basis. It does not correspond to:

- lunar phases,

- solar motion,

- or observable planetary cycles (despite later symbolic associations).

Its widespread adoption originates in ancient Near Eastern tradition and is decisively embedded in the biblical creation narrative (Genesis 1–2).

5.2 Structural strength

Because the week:

- is independent of months and years,

- requires no correction,

- repeats endlessly,

it is immune to calendar drift. Even major calendar reforms rarely alter the weekly cycle (Zerubavel, 1985).

5.3 Implication

The week is socially constructed yet structurally indestructible.

6. Why weeks do not fit months

6.1 The arithmetic reality

- Lunar month ≈ 29.53 days

- Week = 7 days

29.53 ÷ 7 ≈ 4.218 weeks

This makes it impossible for months to contain a consistent number of weeks:

- some months span 4 weeks,

- others overlap into a fifth.

Attempts to impose uniformity (e.g. 28-day months) inevitably:

- distort seasons,

- accumulate error,

- or require disruptive correction.

6.2 Implication

“Weeks per month” is not a natural category but a planning convenience imposed by modern administration.

7. Hierarchies of time: what calendars must prioritise

Every calendar implicitly answers a hierarchy question:

Which unit of time governs the others?

| Priority | Resulting emphasis |

|---|---|

| Day | Universality |

| Week | Rhythmic identity |

| Month | Lunar coherence |

| Year | Seasonal stability |

Conflict arises when:

- weeks are forced to obey months,

- months are forced to obey years,

- or festivals are forced to obey administration.

These conflicts are not mathematical accidents; they are cultural and theological decisions.

8. Comparative consequences

- Biblical systems protect the week (Sabbath) at all costs.

- Islamic systems protect lunar months, accepting seasonal drift.

- Imperial systems protect the solar year for taxation and governance.

- Cosmological systems protect harmony, accepting complexity.

Each approach preserves what its culture considers non-negotiable.

9. Concluding insight

Calendars do not fail because humans are bad at mathematics. They struggle because time itself is not divisible into clean human units. Days, weeks, months, and years originate from different realities, and no calendar can reconcile them without compromise.

Understanding how calendars work is therefore the prerequisite for understanding why dates drift, why religious calendars disagree, and why reform is always contested.

References

Richards, E.G. (2013) Mapping Time: The Calendar and Its History. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Stern, S. (2012) Calendars in Antiquity: Empires, States, and Societies. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Zerubavel, E. (1985) The Seven Day Circle: The History and Meaning of the Week. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.