Authority, Renewal, and the Beginning of the Year

1. Introduction: the New Year as a decision, not a discovery

A “year” is an astronomical reality; a New Year is a cultural, political, and theological decision. While the Earth’s orbit around the sun is fixed, the designation of when a year begins reflects deeper assumptions about authority, renewal, and order. Across civilisations, New Year observance has functioned as a moment of recalibration: of power, morality, cosmic harmony, or social coordination.

This post argues that New Year traditions are best understood not as festive conventions but as expressions of how societies believe time itself should be governed.

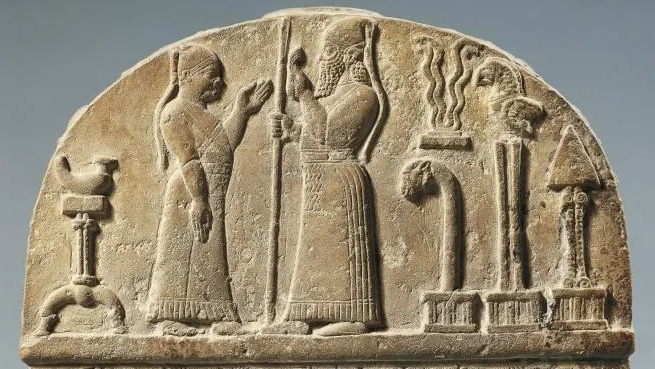

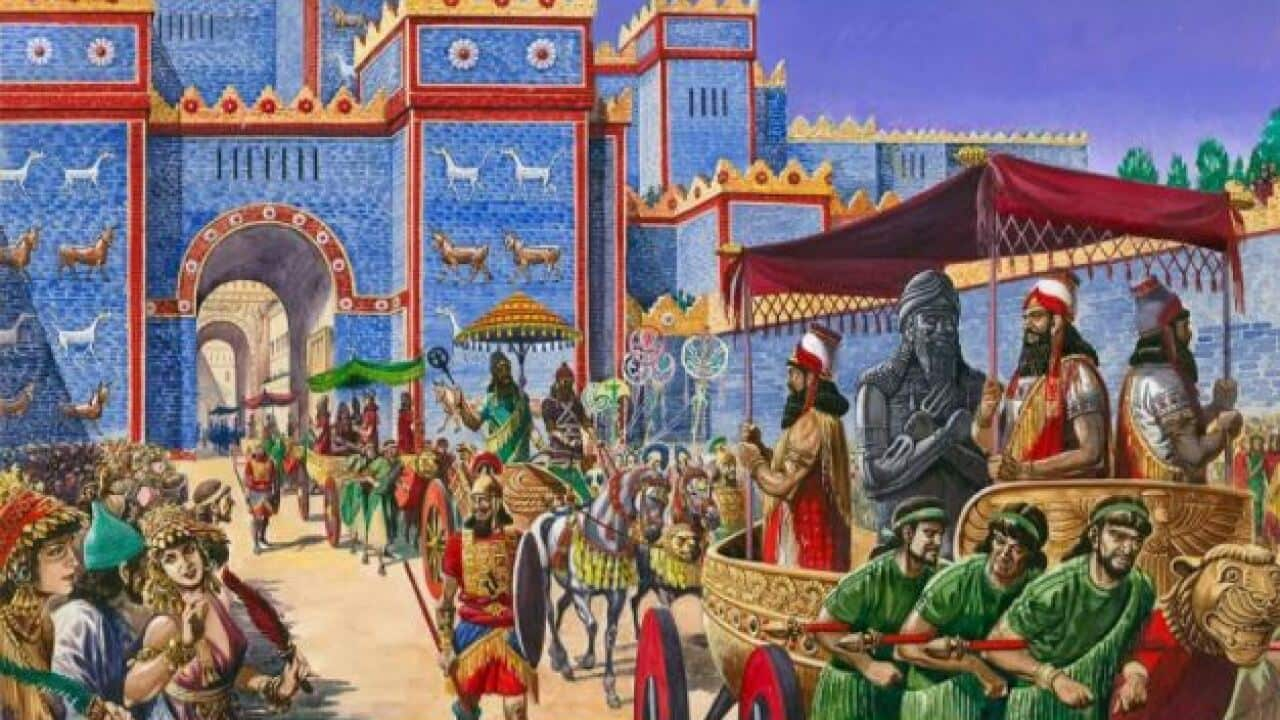

2. The earliest New Year: Mesopotamia and the restoration of order

The earliest recorded New Year celebration appears in ancient Mesopotamia, particularly in Babylon, around the third millennium BCE. The Akitu festival, celebrated in spring, combined agricultural renewal with political and theological affirmation.

Akitu was not a celebration of optimism. It was a ritual response to a worldview in which cosmic order was perpetually threatened by chaos. During the festival:

- kingship was symbolically suspended and restored,

- divine favour was ritually sought,

- and the cosmos was re-stabilised through cultic drama.

Scholars emphasise that Akitu functioned as a cosmogonic renewal rite, reaffirming both the gods’ victory over chaos and the legitimacy of earthly rule (Black and Green, 1992; Stern, 2012). The New Year here served as a mechanism of order maintenance, not personal transformation.

3. Egypt: New Year as astronomical and agricultural synchronisation

In ancient Egypt, New Year reckoning was anchored to the heliacal rising of Sirius, which coincided closely with the annual flooding of the Nile. This flood was essential for agricultural survival and state stability.

Unlike Mesopotamia, Egyptian New Year logic was less concerned with ritual combat against chaos and more with predictable cosmic regularity. Time was governed by the heavens, not renegotiated annually by cultic drama. New Year marked the recognition of an astronomical signal, not a social decision (Belmonte, 2009).

Here, authority resided in cosmic order (Ma’at) rather than in ritual re-enactment. Renewal was not moral or political but life-sustaining and cyclical.

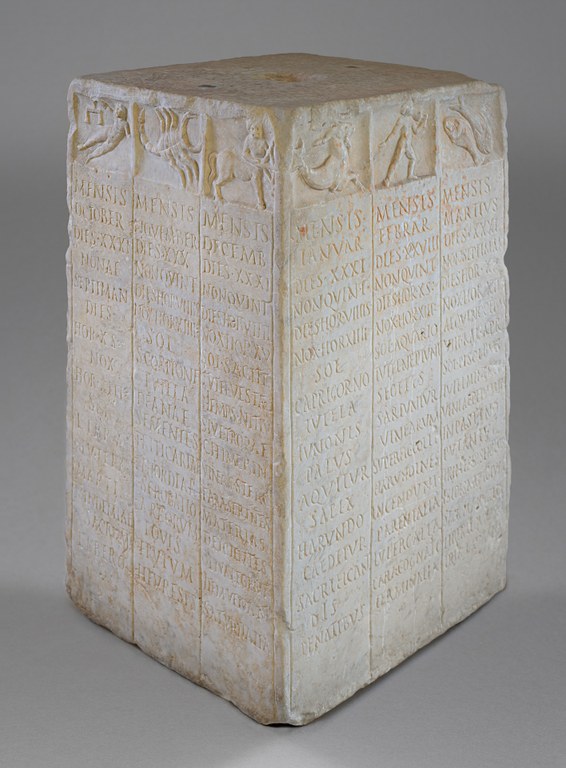

4. Rome: when the New Year became administrative

Early Roman practice began the year in March, aligned with agriculture and warfare. However, in 153 BCE, Rome shifted the beginning of the year to January, named after Janus, the god of thresholds. This shift coincided with the inauguration of consuls, explicitly linking the New Year to civic authority.

The reform reached its definitive form under Julius Caesar, whose Julian calendar standardised the year for imperial administration. This marked a crucial transformation:

- the New Year served governance rather than cosmology,

- time became an instrument of political coordination.

The modern civil New Year (1 January) is a direct descendant of this Roman administrative logic (Richards, 2013).

5. Biblical Israel: New Year without absolutisation

Biblical Israel presents a distinctive pattern: no single New Year dominates sacred time. Instead, Scripture identifies multiple “beginnings”:

- Creation (Genesis 1–2),

- Redemption (Exodus 12:2),

- Agricultural cycles (Leviticus 23).

Later Jewish tradition identifies Rosh Hashanah as the New Year, but even here the emphasis is not festivity but judgement, repentance, and covenant renewal. The New Year initiates the High Holy Days rather than a celebratory reset.

This reflects a covenantal theology of time: renewal is achieved through alignment with God’s will, not through cosmic repetition or administrative decree (Heschel, 1951; Stern, 2012).

6. Other religious New Years: harmony, submission, and cycle

Across other major traditions, New Year observance reflects distinct priorities:

- Islamic (Hijri) New Year: a commemorative marker of the Hijra, observed without mandated celebration; time is subordinated to divine command rather than seasonal logic (King, 2008).

- Chinese New Year: a lunisolar festival emphasising harmony, prosperity, and cyclical renewal within a cosmological framework (Needham, 1959).

- Hindu New Years: multiple regional observances, reflecting a worldview in which time is cyclical and cosmically repetitive rather than linear (Pingree, 1981).

In each case, the New Year encodes a theology of what renewal means.

7. The modern New Year: renewal without authority

In contemporary secular culture, the New Year is globally synchronised but theologically evacuated. It combines:

- Roman administrative structure,

- residual religious language (“resolutions”),

- and commercial spectacle.

Renewal is framed psychologically rather than morally or covenantally. There is no authoritative account of why renewal should occur, only that it should feel hopeful. Time is reset rhetorically, not ontologically.

8. Comparative synthesis

| Culture | What the New Year Reaffirms |

|---|---|

| Mesopotamia | Cosmic order over chaos |

| Egypt | Astronomical regularity |

| Rome | Political administration |

| Biblical Israel | Covenant and repentance |

| East Asian traditions | Harmony and fortune |

| Modern secular | Psychological optimism |

The New Year always answers a single question: who governs time, and by what right?

9. Concluding insight

The New Year is never merely a date. It is a public declaration of authority over time. Whether that authority belongs to gods, cosmos, state, covenant, or the self determines what renewal means—and whether it has any binding force.

References

Belmonte, J.A. (2009) ‘The Egyptian civil calendar: a masterpiece of time organisation’, Astronomical Society of the Pacific Conference Series, 409, pp. 116–130.

Black, J. and Green, A. (1992) Gods, Demons and Symbols of Ancient Mesopotamia. London: British Museum Press.

Heschel, A.J. (1951) The Sabbath: Its Meaning for Modern Man. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

King, D.A. (2008) In Synchrony with the Heavens: Studies in Astronomical Timekeeping and Instrumentation in Medieval Islamic Civilisation. Leiden: Brill.

Needham, J. (1959) Science and Civilisation in China, Vol. 3. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Pingree, D. (1981) Jyotiḥśāstra: Astral and Mathematical Literature. Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz.

Richards, E.G. (2013) Mapping Time: The Calendar and Its History. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Stern, S. (2012) Calendars in Antiquity: Empires, States, and Societies. Oxford: Oxford University Press.