Who Governs Time, Why Alignment Matters, and What Happens When Authority Fractures

1. Introduction: time is never neutral

Across all the preceding posts, one conclusion has steadily emerged: time is not merely measured; it is governed. Calendars are not passive reflections of astronomical reality but active frameworks that encode authority, identity, and meaning. When societies organise time, they implicitly answer three questions:

- Who has the authority to define time?

- What does it mean to be aligned with that time?

- What happens when authority over time fragments?

This final post synthesises the series by showing that authority determines alignment, alignment sustains communal coherence, and the meaning of time collapses when authority is reduced to convenience or power alone.

2. Authority: the power to declare time

2.1 Observation is not authority

Astronomical events—sunrise, new moon, equinox—can be observed by anyone. Calendars, however, require declaration. Someone must decide:

- when a day begins,

- when a month is declared new,

- whether correction (intercalation) is required,

- which approximation binds the community.

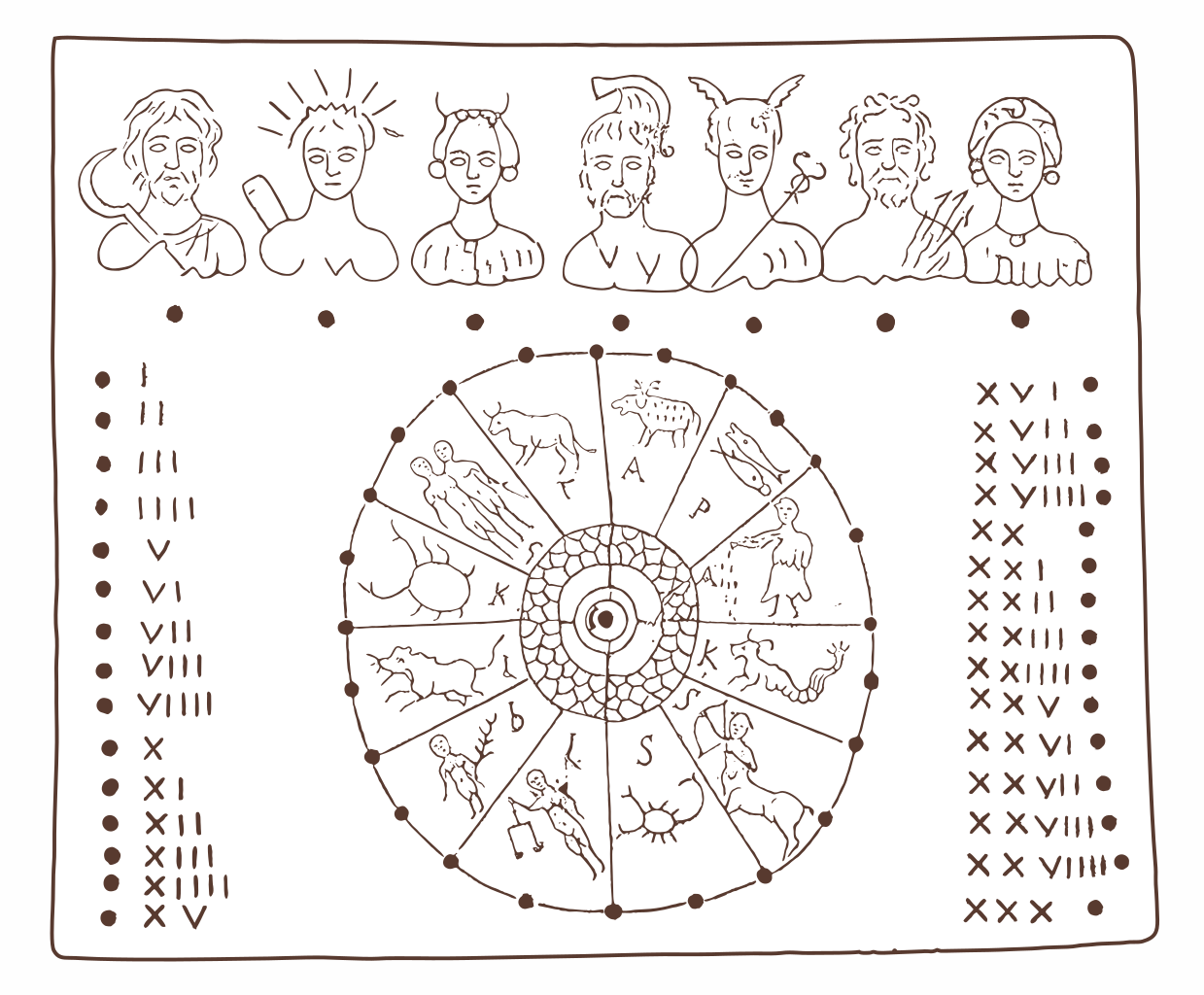

Throughout history, this authority has been exercised by:

- priesthoods (ancient Israel),

- temples and kings (Mesopotamia),

- ecclesiastical councils (Christianity),

- scholarly consensus (Islamic jurisprudence),

- civil states (modern secular calendars).

Without authority, observation produces plurality, not unity (Stern, 2012).

3. Alignment: shared rhythm, not perfect precision

3.1 What alignment actually means

Alignment does not mean astronomical exactness. No calendar achieves that. Alignment means conformity to an authorised rhythm that binds a community together.

A festival can be:

- astronomically approximate,

- mathematically imperfect,

yet still be ritually correct if it aligns with the authorised rule set.

Thus, alignment is relational before it is technical. It synchronises people, not planets.

3.2 Drift as tolerated misalignment

Calendar drift becomes a problem only when it threatens what a community considers sacred:

- seasons (agriculture),

- memory (redemptive history),

- rhythm (weekly rest).

Where drift does not violate core commitments, it is tolerated (e.g. Islamic seasonal rotation). Where it does, correction is enforced (e.g. lunisolar intercalation). Alignment reveals priority.

4. Covenant logic: biblical time as relational obedience

In the biblical worldview, time is governed not primarily by cosmology but by covenant. Covenant presupposes:

- a personal authority (God),

- a revealed will,

- a communal obligation to align life—including time—with that will.

The Sabbath, rooted in creation and remembered in law, exemplifies this logic. It requires no astronomical calculation and no central institution. Observance itself constitutes alignment.

This contrasts sharply with pagan systems, where time is governed by impersonal cosmic cycles and alignment is achieved through ritual repetition rather than obedience (Eliade, 1959).

5. Authority failure and calendrical fragmentation

When authority fractures, calendars fragment.

Historical examples include:

- competing Jewish calendars in the Second Temple period,

- East–West Christian divergence in Easter calculation,

- regional disagreement in lunar observation within Islam.

In each case, the astronomy remained the same. What differed was jurisdiction. Calendrical disagreement is therefore a sign of contested legitimacy, not scientific confusion (VanderKam, 1998).

6. Sunday and continuity without rupture

The Christian shift from Sabbath to Sunday illustrates the distinction between rhythm and designation. The seven-day cycle was preserved intact; only its theological focus changed. There was no “week zero”, no reset of time—only a reorientation of meaning.

This confirms a core principle of the series:

Rhythms rooted in creation endure; designations rooted in authority can change without breaking the rhythm.

7. Modern secular time: authority without meaning

Modern secular society inherits:

- Roman administrative time,

- Christian calendrical structure,

- industrial clock discipline.

What it lacks is transcendent authority. Time is governed by efficiency, productivity, and coordination rather than covenant, cosmos, or moral order. The result is:

- global synchronisation,

- psychological alienation,

- ritual without binding meaning.

The modern New Year exemplifies this: renewal is proclaimed, but no authority defines what renewal entails or why it matters.

8. Synthesis: authority is the hidden constant

Across all systems examined—biblical, pagan, religious, secular—the same pattern holds:

- Authority defines time

- Alignment sustains community

- Fragmentation erodes meaning

Calendars fail not when they drift astronomically, but when they lose the authority capable of declaring alignment worth keeping.

9. Concluding insight: time as confession

Every calendar is a confession of allegiance. It declares who rules time, what is worth remembering, and how life should be ordered. When authority is coherent, time carries meaning. When authority collapses, time becomes mere sequence.

The question is therefore not which calendar is correct, but:

Whose authority gives time its meaning—and what kind of alignment does that authority demand?

References

Eliade, M. (1959) The Myth of the Eternal Return: Cosmos and History. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Stern, S. (2012) Calendars in Antiquity: Empires, States, and Societies. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

VanderKam, J.C. (1998) Calendars in the Dead Sea Scrolls: Measuring Time. London: Routledge.

Zerubavel, E. (1985) The Seven Day Circle: The History and Meaning of the Week. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.