East Germany’s Integration into West Germany: Historical Context, Political Transition, and Socioeconomic Impact

Introduction

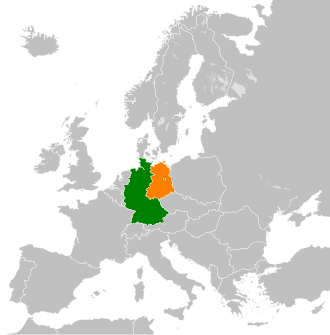

The reintegration of East Germany (German Democratic Republic – GDR) into West Germany (Federal Republic of Germany – FRG) following the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 remains one of the most transformative events in late twentieth-century European history. After over four decades of political, ideological, and economic division, the reunification of Germany in 1990 not only restored national unity but also redefined the geopolitical landscape of post-Cold War Europe. This article examines the historical roots of German partition, the key causes leading to reunification, and the multifaceted consequences—economic, political, and social—of East Germany’s absorption into the West German system.

Historical Background

In the aftermath of the Second World War, Germany was divided among the Allied powers. This division solidified into two separate states by 1949:

- West Germany (FRG) – aligned with NATO and Western capitalist democracies, adopting a federal parliamentary system.

- East Germany (GDR) – a socialist state aligned with the Soviet Union, governed by the Socialist Unity Party (SED) with a centrally planned economy.

The Berlin Wall, erected in 1961, became the most powerful symbol of the Cold War, physically and ideologically separating East from West. While West Germany experienced rapid economic growth and increasing political freedoms, East Germany stagnated under an oppressive regime marked by widespread surveillance through the Stasi (secret police), curtailed civil liberties, and chronic economic inefficiency.

Key Causes of Reunification

- Economic Disparities

East Germany’s economy lagged far behind that of the FRG. Persistent shortages, obsolete industry, and a lack of consumer goods led to growing public dissatisfaction and a desire for the prosperity visible in West Germany. - Popular Resistance and Political Discontent

Throughout the 1980s, East Germans began demanding democratic reforms. The peaceful Monday Demonstrations in Leipzig and other cities showcased the growing momentum of grassroots protest against authoritarian governance. - Collapse of the Berlin Wall (1989)

A combination of internal pressure and external diplomatic signals led to the fall of the Berlin Wall on 9 November 1989. This event symbolised the collapse of the GDR regime and opened the pathway to unification. - Geopolitical Realignment and Diplomacy

The Two Plus Four Agreement (1990)—involving the two German states and the four Allied powers (USA, UK, France, USSR)—ensured the external legal framework for reunification. Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev’s reforms and non-intervention policy were instrumental in facilitating a peaceful transition.

Effects of the Transition

Economic Impact

- The integration of the GDR into the FRG revealed deep structural weaknesses in the East German economy. Massive state subsidies from the West were required to stabilise the region.

- The Treuhandanstalt (Trust Agency) oversaw the privatisation of state-owned enterprises in the East, but this led to widespread unemployment and social dislocation.

- Billions of euros were invested in infrastructure, public services, and urban renewal, yet regional disparities persisted well into the 21st century.

Political and Social Changes

- The legal and constitutional framework of the FRG was extended to the East, bringing democratic institutions, civil rights, and a pluralist political culture.

- Transitional justice efforts led to the prosecution of former GDR officials, particularly for abuses associated with the Stasi and border killings.

- Despite legal unification, cultural and psychological divisions—often referred to as “Mauer im Kopf” (the wall in the mind)—persisted, with differing worldviews and historical narratives between East and West Germans.

International Responses

- Western allies, especially the United States and the United Kingdom, broadly welcomed reunification, viewing it as a triumph of liberal democracy over authoritarianism.

- The Soviet Union, despite initial reluctance, ultimately acquiesced under economic and political pressure, seeing reunification as a necessary concession in the broader context of internal reform and geopolitical retreat.

- Other European states, notably France and the UK, expressed concerns about the rise of a larger, unified Germany but accepted the transition under assurances of continued European integration—eventually leading to the Maastricht Treaty (1992) and the formation of the European Union.

Conclusion

Germany’s reunification stands as a defining moment in the post-Cold War order. It represented not only the collapse of a divided Europe but also the promise and challenges of integrating disparate political systems, economies, and identities. While reunification achieved formal national unity, it initiated a long-term process of social reconciliation and economic balancing. East Germany’s incorporation into the Federal Republic illustrates both the triumph of democratic transformation and the enduring complexity of bridging internal divisions shaped by decades of ideological separation.