Greenland’s Exit from the EEC: Causes, Consequences, and Global Implications

Introduction

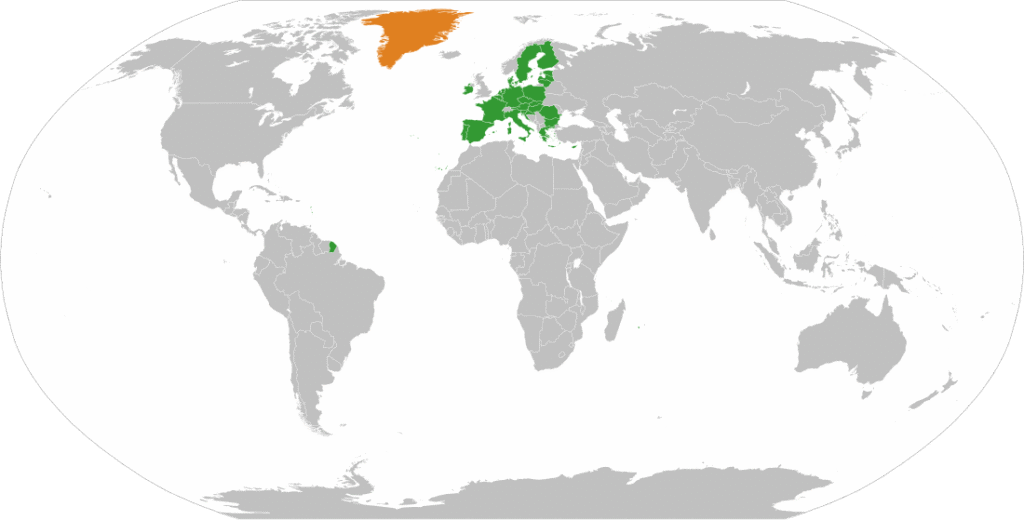

In 1985, Greenland became the first region to withdraw from the European Economic Community (EEC), the precursor to the European Union. Unlike more recent cases such as Brexit, Greenland’s departure was quiet but significant, driven primarily by concerns over fishing rights, national autonomy, and economic sovereignty. This article analyses the causes, consequences, and international reactions to Greenland’s historic exit from European integration.

1. Why Did Greenland Leave the EEC?

1.1 Fisheries and Economic Dependence

Greenland’s economy relies heavily on fishing, particularly cod and shrimp exports, which account for the majority of its GDP. EEC policies imposed fishing quotas and access regulations, allowing foreign vessels to operate in Greenlandic waters. This prompted widespread resentment among local fishermen, who felt these rules compromised their livelihoods.

1.2 Political Autonomy and National Identity

After achieving home rule in 1979, Greenland began asserting its political identity distinct from Denmark. Growing nationalist sentiment led to demands for greater self-determination, particularly in economic and environmental policy-making—areas increasingly shaped by Brussels regulations.

1.3 The 1982 Referendum

In 1982, a national referendum resulted in a 53% majority vote to leave the EEC. This outcome signalled a broader rejection of EEC governance and an aspiration to pursue direct trade relations and autonomous resource management.

2. Economic Consequences of Withdrawal

2.1 Loss of EEC Subsidies

Withdrawal meant Greenland lost access to EEC development funds, which had supported infrastructure and modernisation. However, Denmark maintained financial aid, cushioning the economic impact.

2.2 Bilateral Trade and Resource Control

Greenland successfully negotiated bilateral agreements, preserving trade in fish products and asserting sovereignty over its exclusive economic zone (EEZ). Though trade initially slowed, the territory stabilised through self-regulated fishing exports.

2.3 Labour and Employment Trends

Concerns over job losses proved temporary. Greenland’s labour market adjusted to new regulatory freedom, enabling the development of locally controlled fishing cooperatives and a resilient resource economy.

3. Political and Institutional Outcomes

3.1 Strengthened Self-Governance

The exit reinforced Greenland’s autonomy within the Kingdom of Denmark, reducing external influence from European institutions. This paved the way for greater internal political agency, particularly in fisheries, environmental protection, and trade.

3.2 New Diplomatic Alignments

Outside the EEC, Greenland cultivated closer relations with Nordic and North American partners, aligning its diplomacy with Arctic governance, climate cooperation, and sustainable development priorities.

3.3 EEC and EU Responses

The EEC respected Greenland’s decision, negotiating a new fisheries agreement to preserve mutual interests. Greenland continued participating in European affairs through partnership frameworks, despite its non-member status.

4. International Reactions

4.1 Denmark’s Role

As Greenland’s sovereign state, Denmark facilitated the exit process, provided economic support, and ensured continuity in diplomatic representation.

4.2 Nordic Countries and Arctic Neighbours

Nations such as Iceland and Norway observed Greenland’s fisheries policy with interest, recognising the potential of bilateral Arctic agreements outside EU frameworks.

4.3 United States and Canada

Greenland’s withdrawal opened the door for direct trade and research collaboration in areas such as Arctic fisheries, indigenous policy, and environmental conservation.

5. Migration and Labour Market Effects

5.1 Minimal Migration Disruption

Greenland’s demographic and labour links were primarily with Denmark, not other EEC states. As such, exit from the EEC caused little migration or residency upheaval.

5.2 Labour Policy Autonomy

With fewer external constraints, Greenland tailored labour regulations to fit its economic and cultural context, prioritising employment in fisheries and public services.

5.3 Long-Term Economic Stability

Through resource control and targeted governance, Greenland achieved a stable post-EEC economy, preserving its core industries and minimising outward migration.

Conclusion

Greenland’s 1985 exit from the EEC stands as a unique case of territorial withdrawal from European integration, driven by resource sovereignty, economic autonomy, and national identity. Although initially dependent on Danish financial support, Greenland has since evolved into a self-governing territory with strategic control over its fisheries and foreign relations. Its exit offers an important precedent in international law and policy, particularly in the context of Brexit and other sovereignty movements.